The Compute Wall

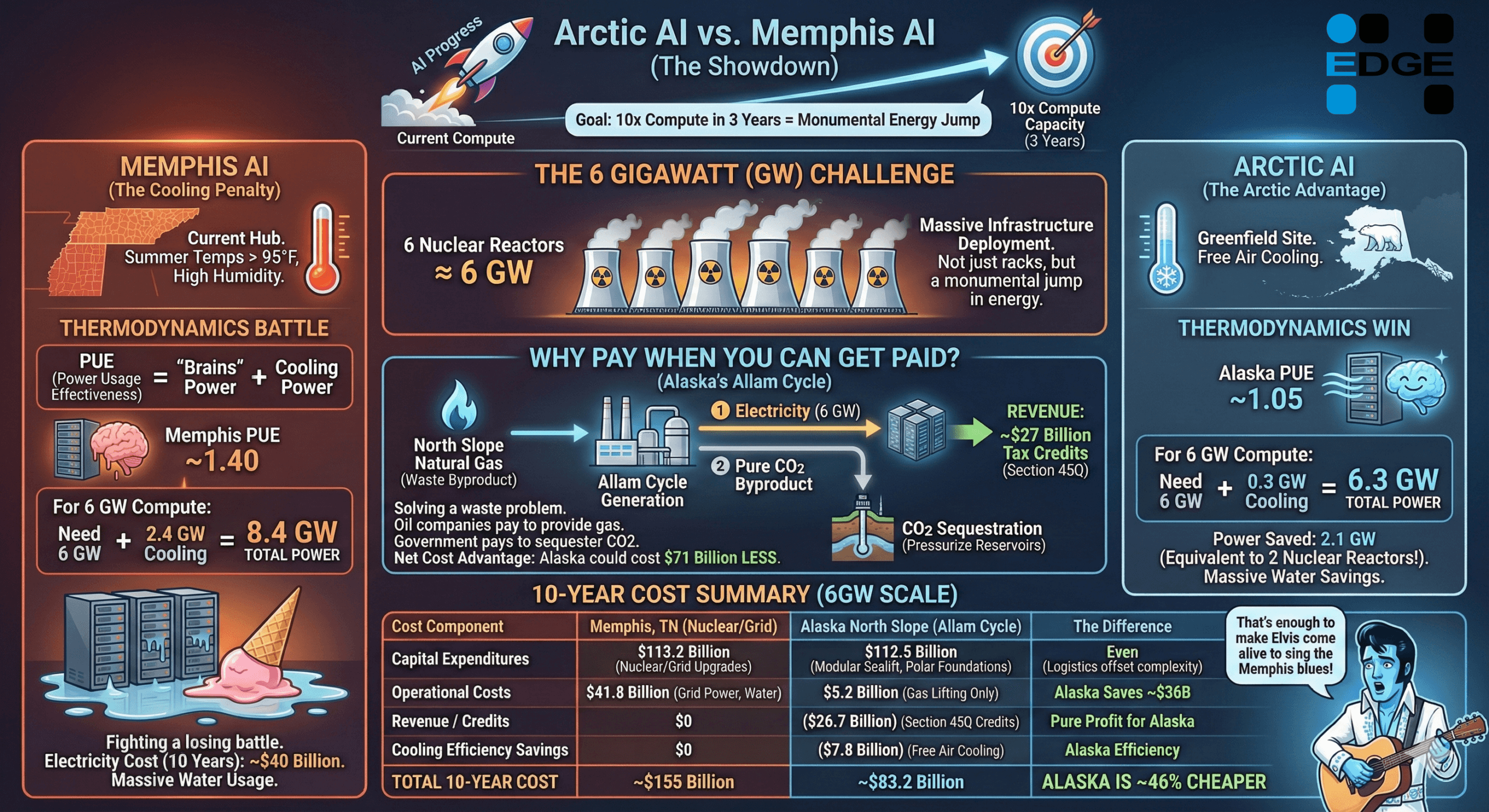

The recent discussions about the near future of AI aren’t just about building the compute, it’s about how to power it. Right now, we are still in that predictable phase of AI development that follows the trend of “increased parameter count means increased ability.” We all know this concept well; it echoes the history of computing, where more transistors meant more capability. It is the very correlation that birthed Moore’s Law.

However, that law is hitting a wall. Historically, we would expect double the compute every two years, however recent years have seen that slow to a meager 15 to 20% gain every 18 months. To compensate, NVIDIA introduced a brute-force approach: massive parallelism. Instead of just bigger and faster chips, they decided to use more chips. Massive amounts of them. I mean NVIDA has ridden this brute-force approach to be one of the world’s most valuable companies.

There is clearly plenty of financial interest and open wallets to push this technology to its limits. But those limits are arriving as fast as the AI advancements themselves. The current “AI Factories” are hitting a ceiling defined not by silicon, but by physics and infrastructure: power, cooling, water, and public goodwill.

It is no longer just a question of “Can we build the chips?” It is now, “How do we cool them?” and “Where do we find the gigawatts to power them?”

Local governments are becoming wary of hosting these resource-hungry facilities. How do you tell your constituents their local power and water are being siphoned off to fuel the very thing that might take their jobs? This is a hard sell. We are about three years away from a hard stop where public goodwill evaporates and the “Not In My Backyard” (NIMBY) effect grinds progress to a halt.

The Space Solution

And Its Thermal Problem

Elon Musk has acknowledged these constraints and proposed a bold solution: Data Centers in Space, or as I like to coin it, “Space AI”.

On paper, this makes sense. In orbit, you have unlimited space (pun intended), unlimited solar power, and no NIMBY regulations. However, there is a technical catch. While space is cold, it is also a vacuum. A vacuum acts like a thermos; it keeps heat in. On Earth, we use air (convection) to cool chips. In space, you can only use radiation, which is inefficient and requires massive surface area.

Then there is the issue of the location itself: Space. Space is far. Space is slow. Space is expensive. Space is just hard.

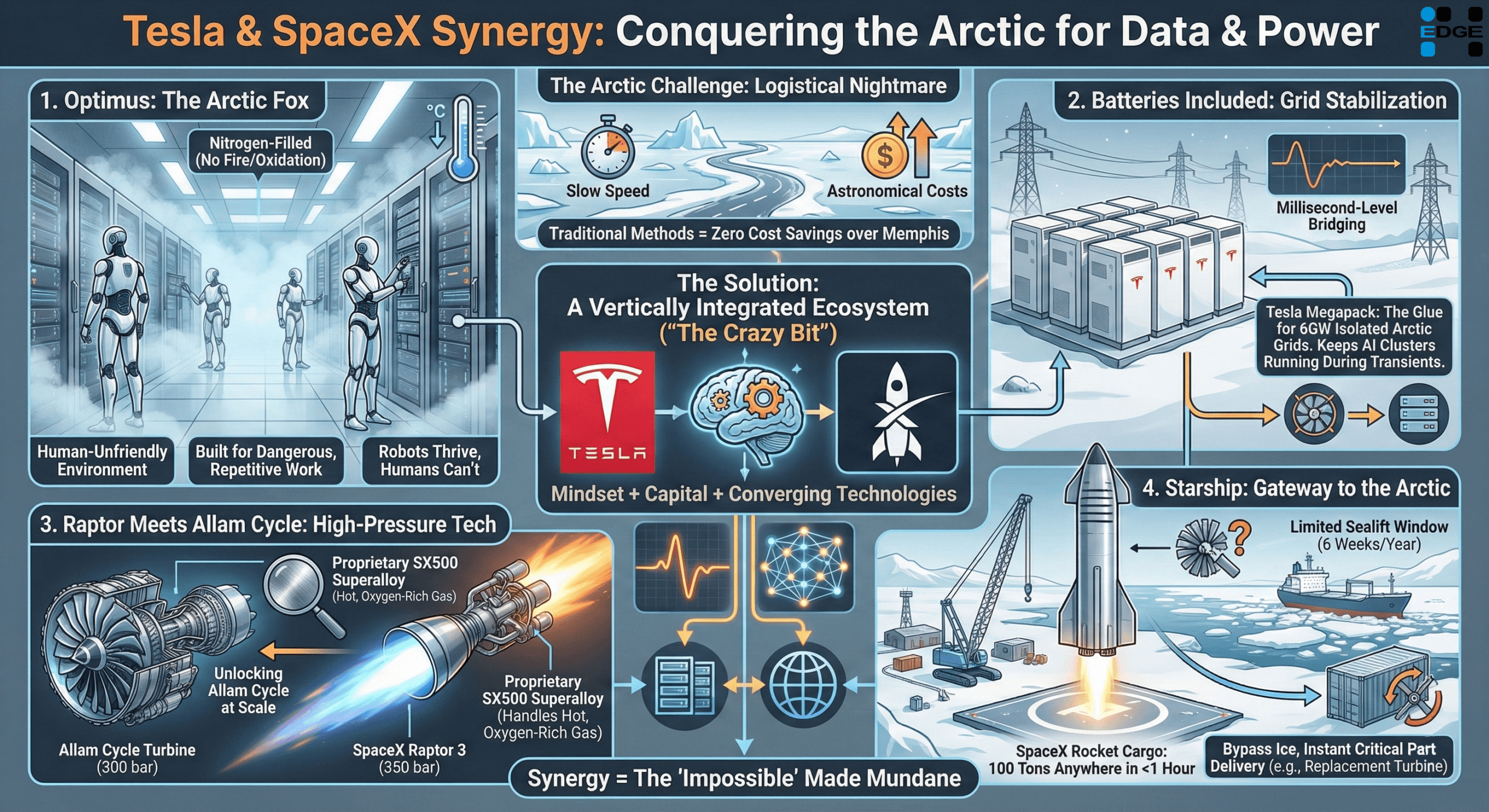

To be fair, “hard” is the native language of Tesla and SpaceX. It wasn’t long ago that their corporate missions were mocked as fever dreams. Yet they didn’t just accomplish these incredible engineering feats, they made them profitable. If anyone could pull off orbital data centers, it’s the team that lands rockets on boats or catches them mid-air with giant mechanical arms.

But while they have dominated the engineering, the calendar is a different story. Timelines are not exactly Elon’s strong suit. Doing the impossible is one thing; predicting when you’ll do it is another. Remember 2015? Elon estimated we were two years away from full self-driving. That prediction was off by a factor of five, turning a “soon” into a decade of “almost there.”

There is a lot to be done to get data centers in space working. Elon says they can do it in three years, which in real-life is likely closer to a ten-year-plus problem. That leaves a massive gap between the AI compute wall we are hitting now and the solution that might arrive 7 years too late.

This begs the question: What do we do in the meantime? What is the 10-year bridge that makes sense not just as a backup, but as a superior alternative?

The Arctic Pivot

Please allow me some backstory. In some ways, my mind is susceptible to the same thing a computer is susceptible to: malware.

The malware just installed itself, I swear I didn’t click that link…and suddenly it consumes your CPU cycles, doing someone else’s bidding. Random bits of information and unsolved problems hijack my brain. Occasionally, one such problem drops onto another, and then another, creating a mental snowball of potential solutions that goes careening through my mind. These become “problutions” that is, problems plus potential solutions. The only way to debug the system is to put pen to paper.

So, what convergence of “problutions” have been tumbling down my mental slope? As a mechanical engineer who loves computers, AI, rockets, and EVs, the challenge of cooling CPUs has always occupied its own “mental cubicle.” Since my previous professional work as a building engineer involved massive industrial cooling systems, and not microchips, there didn’t seem to be much opportunity for cross application.

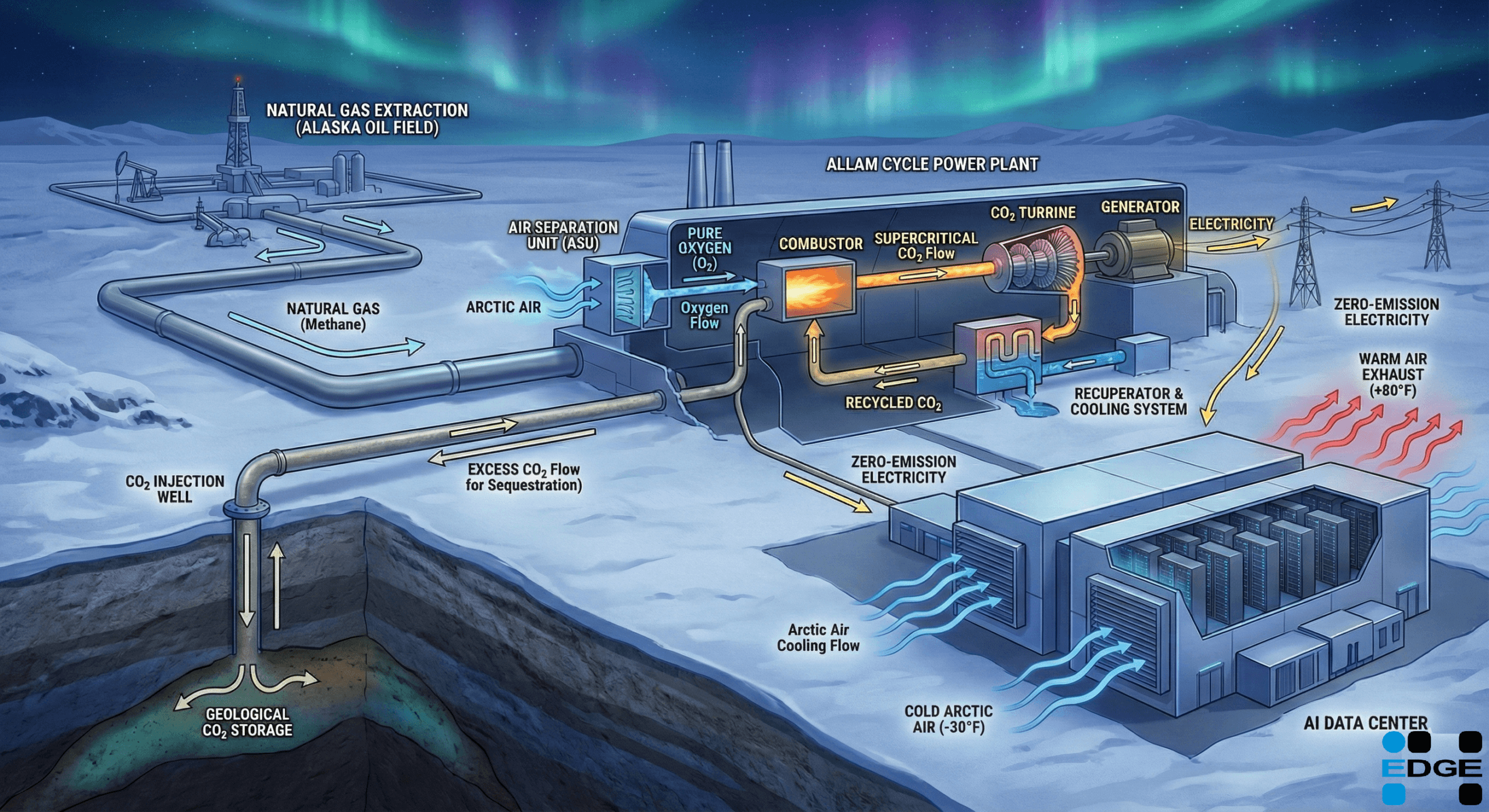

Then came the career pivot. Years ago, I strayed from pure engineering into project management. This path landed me in Alaska, working with giants like Chevron, ConocoPhillips, and BP on North Slope pipelines, oil rigs, and onshore processing. Managing teams of engineers expanded my knowledge of upstream and downstream oil production. And while doing this work, I learned something that immediately demanded its own room in my brain.

The Gas Problem – or Opportunity?

In the process of extracting oil, operators bring up massive amounts of natural gas – around 60 million tons a year. So, what happens to it? They process it, clean it, and inject 90% of it right back into the ground. We are talking about three trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas caught in a loop annually. In 2026 dollars, that is $10 to $30 billion worth of energy buried every year. [^3] [^4]

If you were to burn that gas in turbines at just 50% efficiency, you would generate 500 Terawatt-hours (TWh) of power. That is enough to power one-third of all U.S. homes.[^5][^6] Of course, burning it all at once would deplete the supply in a decade. But a sustainable approach, using 1.3 Tcf per year, would last nearly 30 years and could produce 200 TWh annually. This is the equivalent output of 30 nuclear reactors.

Those are massive numbers. So why isn’t it being sold? Two words: transport logistics. Building the Alyeska oil pipeline was a major engineering achievement, but it was built in an era of supportive regulations and public opinion. Trying to replicate that today for gas is nearly impossible. Even if you could build a pipeline to the coast, liquefying and shipping it is expensive and complicated. The reality is simple: mucho regulation, nada pipeline, nada market access, nada sales. That is why those vast reserves have been sitting there for decades, untapped. Now, what does this have to do with our topic at hand? I’ll get there in a second.

The Cold Reality

The other thought that wiggled its way into its own mental room is just how cold the North Slope (Prudhoe Bay) really is. One day at work, someone from Legal called me about a portable office that had been installed up north. It turned out the mechanical engineer who designed it had never done Arctic work before and specified standard steel. That is a rookie mistake. It gets so cold up there that standard steel undergoes brittle fracture; if you aren’t careful, you can poke a finger right through a frozen piece of sheet metal, maybe a little exaggerated but you can break it with a punch. Everything on the North Slope bows to this cold reality, from the insulated boots you wear, to the exotic alloys you use, to having to keep the oil warm enough to pump 24/7 every day non-stop.

Then there are the geniuses who make the cold work for them. Take the heat pipes along the Alyeska pipeline: they don’t heat the ground; they actually pull heat out of it to keep the permafrost frozen year-round so the pipeline doesn’t sink. So, my mind started turning: “Hey, that’s massive, free cooling. I wonder what else that could be used for?” Well, one slow day at work, those two thoughts finally collided: unlimited stranded gas and unlimited free cooling